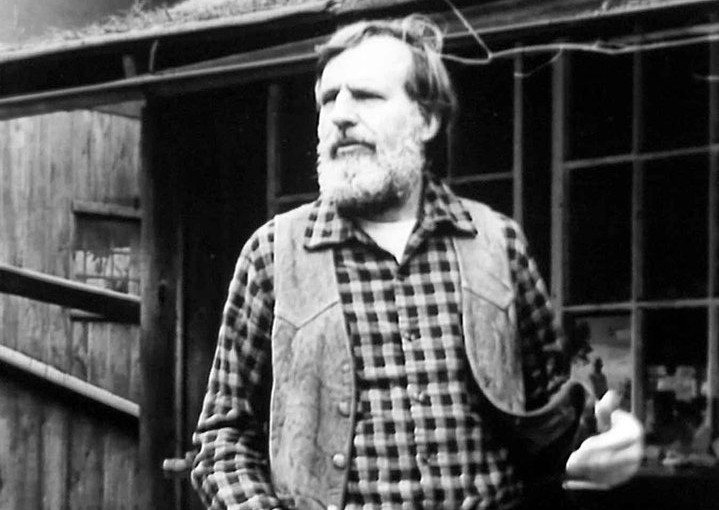

Marcus sat by the window, looking out over the clearing. Another winter thawed outside. He’d seen 92-odd winters come and go in his lifetime, plus a few he didn’t remember. Just the essentials. That’s what he’d told the reporters who’d snowshoed in to report his 95th birthday for the Echo. That’s what kept him alive and fit at the age of 95.

He had his house on the lake, his tools in his shop and plenty of firewood for the winter. No need for foolishness. No need for make-work projects, when there was enough real work to be done.

It had been a surprise when the reporter came up the path, audible before she’d been visible- her snowshoes crunching on the top layer of crusted snow. He recognized her of course. Her was printed next to her column in the paper.

Marcus kept a newspaper subscription for three reasons:

- He liked having something to read in the outhouse (especially if he was snowed in and couldn’t get to town for *ahem* other papers he might want in there)

- He liked the excuse to walk the 400 yards to the end of the driveway every morning.

- It was nice to have an alernative source of kindling in case birch bark supplies were running low.

The last reason wasn’t really that strong he reflected after he realized he was following the “rule of three.” It wasn’t strong, because he couldn’t remember the last time that he had actually used birch bark or paper to start a fire. Sure, he kept some around in case of emergency, but he also had as much white gas as he was ever likely to need in the small cottage he’d built all those years before.

Despite the reputation he had (and was largely unaware of) of being the last of the old-time trappers, sourdoughs and voyageurs, Marcus had no pride at all when it came to the practical matter of starting a fire.

He’d happily use a lighter if one was available, but generally preferred to make his own kindling bundles use a steel whenever possible. Small bundles of moss and Jack Pine twigs that would go up like kerosene even soaking wet.

He knew how to use a bow-drill of course and other “primitive” means, but fire was too important to survival for a person to stick to honorable methods like Flint and Steel or even a one-match fire.

Hell, he’d even started a fire using a ball made of thin strips of duct tape he’d ignited with steel wool and a 9-volt battery once. It stank to high heaven and was smokey as hell, so it was probably for the best that he’d pulled it from the one Fire detector that weasel of a bureaucrat Amos Johnson had insisted upon. Damn thing went off half the time when he cooked his bacon, as if he wasn’t perfectly aware it was smoking him out of his own cabin.

In reality of course, Amos was amiable and capable, it’s just that among other duties he was responsible for making sure things were up to code. The way Marcus saw it, code was fine. It was for people who didn’t know how to build a house properly so the damned thing wouldn’t fall down. It didn’t need to apply to people who know what they’re doing.

There was one other objection Marcus had to Amos. He talked too much. Any time they ran into each other in town, that damned fool said nothing in as many words as possible. He had a nervous manner and talked too loud. Especially outside.

Over the years Marcus had come to realize the truth of silence. Understanding that the bigger the space, the quieter one should be in it. Not space per se, but more like what you get when there’s space and it’s not filled up with people.

Being outside in a city requires a person to be louder to make themselves heard. So, being inside with that mentality, one needs to to remember to be quiet.

Being outside “on the loose” as one of the old campfire songs from his youth had called it, meant that you didn’t need to be loud. Your very presence there was an intrusion, like a stranger at a wake. Everything in the forest is so aware of any human, that there’s no need to be loud. You have the floor, as it were.

This is what that damned fool Amos never seemed to understand.

The reporter had been better. She knew how to listen at least. Well, sort-of. She knew how to listen to people, for what they said and what they said when they didn’t say something. It was a start. Maybe in time, she’d learn to listen without needing to hear words in the silence.

The questions for the article had covered a range of topics. Mostly banal, but some sparked memories he’d forgotten for a long time. Where was he from? The past. What did he do? The work in front of him. (How can you explain to someone the rhythm of living on your own off the land? How can you explain that every day is the same and each day is unique? How you know when to find mushrooms or run trap lines or hunt deer?) The questions had continued for awhile, until she asked her last question. What made you move out here away from everyone? I came seeking silence and a place to think.

At that point, she’d understood his meaning more pointedly than he’d meant to say it, because she started to pack up her notebook. Quickly. “Well, thank you for your time and I’ll try not to intrude on your silence any further.”

Her snowshoes finally agreed to being used, after a bit of wrangling and she was out the door. He was surprised at how tired he felt tired after she left. Probably just a reaction to an uninvited visitor making him use the long-forgotten courtesy parts of the brain. Janet. That was the name on the columns.

It’s funny how someone can look like a name, he thought. As if the appellation a parent gives a child somehow shapes their character. Then unbidden, memories of his son, his Jack, were called up against his will.

There was no question what he needed to do next. He picked up his axe and went to split logs for firewood.